What did Hong Kong’s corals

look like thousands of years ago?

Ecological restoration, reverting human-modified nature back to its original state, is now taking place worldwide. One of the main goals of ecological restoration is to bring back the lost biodiversity - the number of species an ecosystem supports.

Biodiversity is not only the foundation of an ecosystem’s health and stability. The higher the biodiversity, the better are the services, such as fisheries, that an ecosystem can provide to people.

When restoring land-based ecosystems such as forests, it is relatively easy to know what species of trees we should bring back. In the sea, however, the past is hidden underwater and is much harder to uncover.

Corals are often called underwater forests, and just like the actual forests on land, coral communities and reefs around the world have been shaped by centuries of human activities, such as pollution, land reclamation and on-shore construction.

Coral restoration has been happening since mid-1980s, but, when trying to restore a coral community, little to no effort is made to find out what it may have looked like before the influence of humans. However, the original coral community is likely to have supported higher biodiversity.

In Hong Kong, a new methodology called inferred restoration, developed at the Swire Institute of Marine Science(SWIMS), is changing the understanding of how corals should be restored.

Last year, historical ecologist Dr Jonathan Cybulski from SWIMS reconstructed the change in coral communities in Hong Kong from 5,000 years ago to the present. Cybulski’s research revealed that the coral communities around Hong Kong used to be very different from what they are now.

These findings are now used in a coral restoration project in Hoi Ha Wan Marine Park to infer a target community of coral species and allow the scientists to bring back the original coral fauna of Hong Kong.

“Hong Kong is an incredible case study of human impact on the marine environment,” says Cybulski, “we have extreme human development but also high coral biodiversity.”

Hong Kong boasts the densest urban population on Earth and its waters amount to just 0.03% of China’s total, but they are home to more than 25% of all of China’s marine species, including almost 90 species of coral - more than in the Caribbean.

Cybulski describes the waters around Hong Kong in terms of two distinct regions with very different water conditions. What he calls the South Region - from Lantau Island to just beyond the Eastern tip of Hong Kong Island, is dominated by the murky freshwater outflow of the Pearl River. The East Region - Mirs Bay, is influenced by the open waters of the South China Sea.

The coral communities in the two regions are very different, says Cybulski. The South region has low coral diversity and is dominated by the so-called massive corals, mainly of the genus Platygyra that are shaped like underwater boulders.

The East Region, in contrast, has a much higher diversity of corals, with more than 50 species, including the branching corals of the genus Acropora, known as staghorn corals. These corals resemble small bushes and create a complex 3D environment that supports the high biodiversity typical of coral reefs. Biodiversity in the East Region was much higher than in the South where Acropora was completely absent.

“My question was - is it how is it has always been?” says Cybulski. “A very logical hypothesis is that the murky freshwater (that affects coral growth) from the Pearl river creates this diversity gradient. It seemed very possible that this is not a human story at all.”

To answer this question, Cybulski took samples of cores of the sea bed across the entire span of Hong Kong’s coastal waters, identifying the coral that existed in each location from now to 5,000 years ago.

Cybulski found out that there used to be no South-East diversity gradient at all. A “continuous coral community” once existed all around Hong Kong. Acropora, the crucial habitat builder and promoter of biodiversity, thrived in the South, despite the influence of the Pearl River. The decline of Acropora and the emergence of biodiversity gradient are recent, Cybulski realised, dating to the late 1970s.

As well as tracking the change in the coral communities by identifying the coral fossils from cores, Cybulski also “became a detective” to find out as much as he could about the past of Hong Kong coral communities and the events that may have affected them.

“I asked everyone I could for historical photos, or any type of literature. Searching for ancient areas of coral, I looked through all the nautical maps I could find, because they usually delineate where reefs are.” explains Cybulski.

Hong Kong has excellent water quality records, and Cybulski was able to follow the changes in levels of different chemical compounds through time.

Eventually, Cybulski had three sets of information - what coral species Hong Kong’s coral communities consisted of in the past, what species they consist of now, and how the environment of Hong Kong’s seas changed during that time. Cybulski also built a timeline of events that have, or are likely to have, affected Hong Kong’s corals. It turned out that they have been through a lot.

During the turn of the 19th century, mining of corals for slaked lime was common in Hong Kong with over 40 metric tons harvested annually. In the 1950s, there was a growth of agriculture, both in Hong Kong and in Guangdong Province, greatly increasing the amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus in the seawater. In the 1970’s pig farming boomed in Hong Kong, leading to further organic pollution of the sea.

The 1980s saw massive land reclamation projects, such as the building of the new Hong Kong airport, the world’s largest land reclamation project at that time. These were mainly in the South Region - Lantau Island and Victoria Harbour, and the increased turbidity of the water devastated the local coral. There was no wastewater treatment in Hong Kong until the 1990s, and raw effluent was pumped straight into the sea.

Cybulski then used advanced statistical methods to measure the influence of different factors on the composition of the coral community in time.

He reached a conclusion that this was a “human story” after all. The man-made decline in water quality decimated the habitat-creating branching Acropora corals in the southern part of Hong Kong waters, driving down biodiversity. Neither the warming climate, nor the natural influence of the Pearl River played a part.

Cybulski says that he is often asked to describe what Hong Kong’s corals looked like 5,000 years ago: “My story is the tip of the iceberg, a snapshot of what was here. But I can say that there was a far more coral cover, much more branching corals and much higher biodiversity of coral - associated molluscs, and fish that use corals to hide from prey, lay their eggs, (use it as a) habitat for juveniles. In Hong Kong, we used to have dugongs, booming fish populations, there were sharks, there were massive oyster beds.”

With a long-term view of restoring this former biodiversity, in 2013, SWIMS started a coral restoration program in Hong Kong. The program was commissioned and funded by the Hong Kong’s Agriculture Fisheries and Conservation Department (AFCD). Coral restoration work at SWIMS now runs alongside the restoration of other key coastal ecosystems of Hong Kong - seagrasses, oyster beds and mangroves.

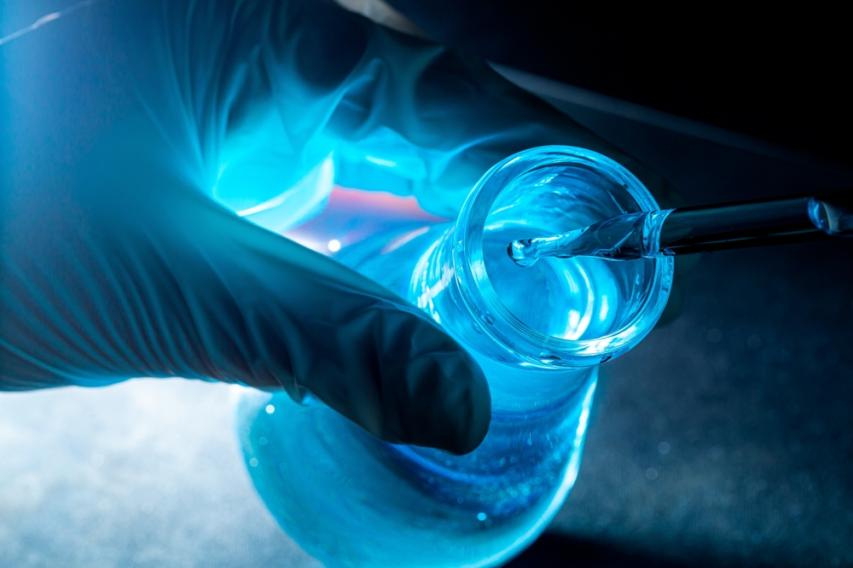

To restore the coral communities of Hong Kong, fragments of corals were planted on 3D-printed clay tiles that were then placed on the sea bed in Hoi Ha Wan Marine Park.

Cybulski’s work was used to decide what combination of coral species should be planted on the tiles.

A key decision was to include staghorn coral - Acropora. This species is very important in maintenance of biodiversity - reefs and communities of Acropora support more species that than other corals do. However, Acropora is now absent from many locations Hong Kong and had not been seen in Hoi Ha Wan since surveys in 2004.

Cybulski’s data was presented to the Marine Park’s Council - which gave permission to reintroduce Acropora sourced from local populations to the Marine Park where they are once again thriving: “We have 100% survival rate of coral,” says Cybulski.

Cybulski is confident that SWIMS’ model - looking into the past to understand the original coral community, and then presenting this knowledge to the authorities to work together with marine scientists to restore the lost biodiversity, can be replicated anywhere in the world.

Article by Dr Pavel Toropov from HKU School of Biological Sciences